CV of Timothy Stephens

I am a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Professor Debashish Bhattacharya at Rutgers University. I specialize in the application and development of multi-omics data analysis workflows to explore foundational biological questions, such as how photosynthesis evolved in eukaryotes, how life evolves in early earth-like hot spring environments, and most importantly, how we can use and explore the natural adaptability of corals to aid their survival and restoration in a world affected by climate change. I am also CEO of OceanOmics, a company dedicated to developing scalable tools for environmental health monitoring.

Active projects

Coral stress response and genome evolution

Coral reef ecosystems are under increasing pressure due to anthropogenic climate chance. With, in recent years the prevalence of thermal stress-related expulsion of the algal symbionts (known as ‘coral bleaching’) increasing and affecting larger and larger amounts of the earths reefs. A prime example of this is seen in the Great Barrier Reef in Australia (see Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is hit with mass coral bleaching yet again by NPR). My work in the Bhattacharya lab, in collaboration with other researchers from around the world, aims to improve our understanding and management of the existing health and stressed coral reef through a number of key projects, that includes: (1) the development of a portable coral stress toolkit that can be deployed easily and cheaply in remote locations; (2) the characterization of hormone regulation patterns associated with coral spawning and their dysregulation during thermal stress; (3) the characteristics of coral genome evolution, with a focus on Hawaiian corals, and how that can be used to understand coral diversity, stress resistance, and the evolution of novel genes and functions (also known as the “dark matter” of the genome); (4) the prevalence and functional consequences of asexual reproduction and variation in ploidy of a weedy coral species from Hawaii and what it tells us about the repertoire of adaptation strategies deployed by corals in the face of climate change and how we might better use this knowledge to inform and support protection and restoration activities; and (5) the exploration and integration of multi-omics (i.e., genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and microbiome) data from corals and the development of strategies for how we can better utilize this information to make informed discoveries about the coral biology and holobiont and their response to stress.

Representative publication

- Ploidy variation and its implications for reproduction and population dynamics in two sympatric Hawaiian coral species. Stephens T. G., Strand E. L., Putnam H. M., and Bhattacharya D. Genome Biology and Evolution, evad149, 2023.

- Peeling back the layers of coral holobiont multi-omics data. *Williams A., *Stephens T. G., Shumaker A., and Bhattacharya D. iScience, 26(9):107623, 2023.

- Facultative lifestyle drives diversity of coral algal symbionts. Bhattacharya D., Stephens T. G., Chille E. E., Benites L. F., Chan C. X. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 39(3):239-247, 2023.

- High-quality genome assembles from key Hawaiian coral species. Stephens T. G., Lee J., Jeong Y., Yoon H. S., Putnam H. M., Majerova E., and Bhattacharya D. GigaScience, 11:giac098, 2022.

- Development of a portable toolkit to diagnose coral thermal stress. Meng Z., Williams A., Liau P., Stephens T. G., Drury C., Chiles E. N., Su X., Javanmard M., and Bhattacharya D. Scientific Reports, 12:14398, 2022.

- Multi-omic characterization of the thermal stress phenome in the stony coral Montipora capitata. Williams A., Pathmanathan J. S., Stephens T. G., Su X., Chiles E. N., Conetta D., Putnam H. M., and Bhattacharya D. PeerJ, 9:e12335, 2021.

- Life on the edge: Hawaiian model for coral evolution. Bhattacharya D., Stephens T. G., Tinoco A., Richmond R., and Cleves P. A. Limnology and Oceanography, 67:1976-1985, 2022.

- Comparison of 15 dinoflagellate genomes reveals extensive sequence and structural divergence in family Symbiodiniaceae and genus Symbiodinium. Gonzalez-Pech, R. A., Stephens T. G., Chen Y., Mohamed A. R., Cheng Y., Shah S., Dougan K. E., Fortuin M. D. A., Lagorce R., Burt D. W., Bhattacharya D., Ragan M. A., and Chan C. X. BMC Biology, 19:73, 2021.

Endosymbiotic Origin of Photosynthetic Organelles

The evolution of photosynthesis in eukaryotes, which occurred when a photosynthetic bacterium became integrated into a eukaryotic host around 1.6 billion years ago, is one of the most pivotal events in the history of life on earth. All photosynthetic plants and algae (which comprise the “supergroup” Archaeplastida) can trace their ancestry back to this single event and there is no question that the evolution of photosynthetic eukaryotes paved the way for the formation of complex multicellular life (such as humans). While we have extensive knowledge of the characteristics and evolutionary forces that define the extant (current) photosynthetic lineages, our understanding of the origins of these groups is lacking due to the extreme age of the endosymbiotic event that gave rise to them and the lack of any intermediate stages of this process. The only known independent example of photosynthetic primary endosymbiosis is found in the amoeba genus Paulinella, which has a lineage that recently (~100 million years ago) captured and retained a photosynthetic cyanobacterial endosymbiont. The relatively young age of the endosymbiosis in Paulinella means that it is at an intermediate stage of its evolution, making it an ideal model for exploring many of the outstanding questions related to the forces that drove the endosymbiosis in the ancestor of Archaeplastida. My work, in collaboration with Arthur Grossman and Victoria Calatrava from the Carnegie Institution (Stanford), focuses on characterizing the forces that drive the genome evolution of the host after acquisition of the endosymbiont. The projects I have worked from this research area include: (1) exploring how functions, shared by both the host and endosymbiont or that are novel to the host, evolve and the forces that govern their outright loss or transfer from the endosymbiont; (2) exploring the evolution of endosymbiont derived genes in the host genes, and the processes through which they become integrated into the hosts systems; and (3) synthesizing novel theories to explain the forces that govern the evolution of the host and endosymbiont during the early stages of endosymbiosis by combining established evolutionary theories with the data available for Paulinella.

Representative publication

- Retrotransposition facilitated the establishment of a primary plastid in the thecate amoeba Paulinella. *Calatreva V., *Stephens T. G., Gabr A., Grossman A. R., and Bhattacharya D. PNAS, 119:e2121241119, 2022.

- Loss of key endosymbiont genes may facilitate early host control of the chromatophore in Paulinella. *Gabr A., *Stephens T. G., and Bhattacharya D. iScience, 25:104974, 2022.

- Why is primary endosymbiosis so rare? Stephens T. G., Gabr A., Calatreva V., Grossman A. R., and Bhattacharya D. New Phytologist, 231:1693-1699, 2021.

- Endosymbiotic ratchet accelerates divergence after organelle origin. Bhattacharya D., Etten J. V., Benites L. F., and Stephens T. G. BioEssays, e2200165, 2022.

Evolution of life in early earth-like hot spring environments

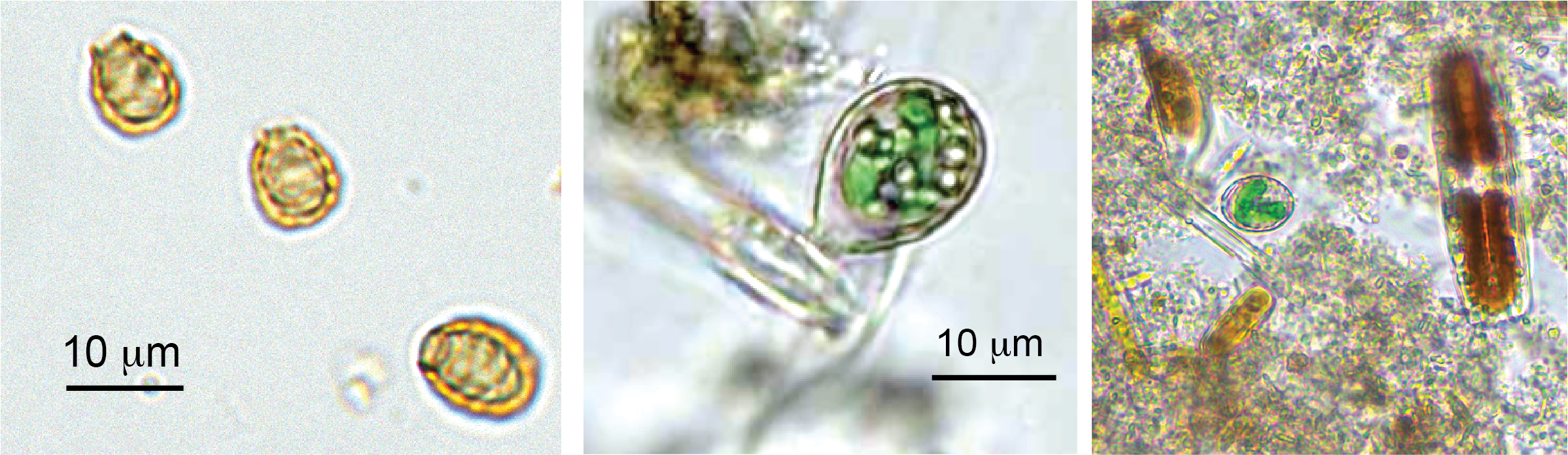

Bacteria and Archaea are usually recognized as the masters of extreme environments, with until recently, eukaryotes, particularly algae, being largely overlooked. Extremophilic red algae in Cyanidiophyceae occupy habitats such as hot springs and acid mine drainage sites that have low light, low pH, high temperature, and high salt and toxic heavy metal concentrations. These conditions, which are inhospitable for most organisms, in particular other photoautotrophs, are virtually the only locations where these organisms can be found. Analysis of genome data has demonstrated that genes transferred horizontally from prokaryotes have contributed to the adaption of Cyanidiophyceae to extreme environments. Nonetheless, much still needs to be learned about how native pathways and regulatory systems in these organisms have evolved in response to extreme conditions and how external biota, such as other extremophilic bacteria and archaea, contribute to their survival. To address this gap in our understanding of Cyanidiophyceae, we worked with collaborators at the Joint Genome Institute and Timothy McDermott from Montana State University to generate meta-genomic, meta-transcriptomic, and meta-metabolomic data from three distinct hot spring habitats at Lemonade Creek in Yellowstone National Park. The projects I have worked on from this research area include: (1) developing a workflow for the integration and analysis of temporal meta-multi-omics data; (2) characterizing the prokaryotic, eukaryotic, and viral (in collaboration with my colleague L. Felipe Benites) diversity and abundance across the sampled environments; and (3) exploring the biosynthetic functions and activity of each species in each environment over the diurnal cycle and how the synergy between the different species combined to form stable, persistent ecosystems.

Bacteria and Archaea are usually recognized as the masters of extreme environments, with until recently, eukaryotes, particularly algae, being largely overlooked. Extremophilic red algae in Cyanidiophyceae occupy habitats such as hot springs and acid mine drainage sites that have low light, low pH, high temperature, and high salt and toxic heavy metal concentrations. These conditions, which are inhospitable for most organisms, in particular other photoautotrophs, are virtually the only locations where these organisms can be found. Analysis of genome data has demonstrated that genes transferred horizontally from prokaryotes have contributed to the adaption of Cyanidiophyceae to extreme environments. Nonetheless, much still needs to be learned about how native pathways and regulatory systems in these organisms have evolved in response to extreme conditions and how external biota, such as other extremophilic bacteria and archaea, contribute to their survival. To address this gap in our understanding of Cyanidiophyceae, we worked with collaborators at the Joint Genome Institute and Timothy McDermott from Montana State University to generate meta-genomic, meta-transcriptomic, and meta-metabolomic data from three distinct hot spring habitats at Lemonade Creek in Yellowstone National Park. The projects I have worked on from this research area include: (1) developing a workflow for the integration and analysis of temporal meta-multi-omics data; (2) characterizing the prokaryotic, eukaryotic, and viral (in collaboration with my colleague L. Felipe Benites) diversity and abundance across the sampled environments; and (3) exploring the biosynthetic functions and activity of each species in each environment over the diurnal cycle and how the synergy between the different species combined to form stable, persistent ecosystems.

Representative publication

- Viruses associated with extremophilic red algal mats reveal signatures of early thermal adaptation. Benites L. F., Stephens T. G., Etten J. V., James T., Christian W. C., Barry K., Grigoriev I. V., McDermott T. R. & Bhattacharya D. Communications Biology, 2024.

- Algae obscura: The potential of rare species as model systems. Etten J. V., Benites F. L., Stephens T. G., Yoon H. S., and Bhattacharya D. Journal of Phycology, 59(2):293-300, 2023.